Col. John W. Ripley USMC/Ret

1939 - 2008

Marine colonel, member of Ranger Hall of Fame,

was known for the destruction of a bridge during

the Vietnam War

constructed from story by Nick Madigan

published November 3, 2008 Baltimore Sun

John W. Ripley, a retired Marine Corps colonel and a renowned hero of the Vietnam War, died at his home in Annapolis over the weekend, family members said. He was 69.

A Virginia native, Colonel Ripley was best known for a daring feat during the Easter Offensive of 1972, when he dangled for three hours under a bridge near the South Vietnamese city of Dong Ha to attach 500 pounds of explosives to the span, ultimately destroying it. His action, under fire while going back and forth for materials, is thought to have thwarted an onslaught by 20,000 enemy troops and was the subject of a book, The Bridge at Dong Ha , by John Grider Miller.

When his son was asked to describe a single quality that defined his father, Mr. Ripley said, "Tenacity."

"He was tenacious in his love for his country, his family and the Marine Corps," said Mr. Ripley, who also lives in Annapolis. "He never did anything halfway."

Earlier this year, Colonel Ripley was inducted into the U.S. Ranger Hall of Fame at Fort Benning, Ga., an honor that he added to his many decorations. They included the Navy Cross, the second-highest combat award a Marine can receive; the Silver Star; two awards of the Legion of Merit; two Bronze Stars; and the Defense Meritorious Service Medal. His tale is required reading for every Naval Academy plebe. In Afghanistan, a forward operating base was named for him.

"I admired John not only because of his obvious war heroism, but because of how he conducted himself after the war," said Thomas L. Wilkerson, a retired major general in the Marines and chief executive of the U.S. Naval Institute. "John was the standard to which we all aspire. There wasn't any baggage around John about how things should go. He walked his own talk."

Another Marine Corps colleague, Ray Madonna, who served with Colonel Ripley in Vietnam and retired as a lieutenant colonel, said he had known him for almost 50 years and had seen him Oct. 25 at the Navy football game against Southern Methodist University in Annapolis.

"He was with a couple of his grandchildren," Mr. Madonna said yesterday. "He looked fine. He was walking a couple of miles a day, building himself back after the surgeries. So it was a total shock."

In July 2002, after unsuccessful transplant surgery, Colonel Ripley's life was saved by a second operation at Georgetown University Medical Center, in which he received a liver from a 16-year-old gunshot victim in Philadelphia. The surgery became possible only after a high-speed military mission transported the organ to Georgetown in a Marine Corps helicopter from the president's fleet.

Colonel Ripley's liver had been damaged by a rare genetic disease as well as by a case of hepatitis B that he believes he contracted in Vietnam.

Describing the Dong Ha incident in a June 2008 interview with Marine Corps Times , Colonel Ripley said he "had to swing like a trapeze artist in a circus."

"I used my teeth to crimp the detonator and thus pinch it into place on the fuse." He said. "I crimped it with my teeth while the detonator was halfway down my throat."

Yesterday, on the Web site of World Defense Review , Maj. W. Thomas Smith Jr., a former Marine infantry squad leader who has researched Colonel Ripley's life, wrote that after Colonel Ripley had set the charges and moved back to the friendly side of the river, the fuses detonated and Colonel Ripley "was literally blown through the air by the massive shock wave" he had engineered.

"The next thing he remembered, he was lying on his back as huge pieces of the bridge were hurtling and cartwheeling across the sky above him," Major Smith wrote.

Major Smith quoted an interview that Colonel Ripley gave for Americans at War , published by the Naval Institute, in which he said: "The idea that I would be able to even finish the job before the enemy got me was ludicrous. When you know you're not gonna make it, a wonderful thing happens: You stop being cluttered by the feeling that you're going to save your butt."

Colonel Ripley was shot in the side by a North Vietnamese soldier and during two tours of duty was pierced with so much shrapnel that doctors found metal fragments in his body as recently as 2001. After Vietnam, Colonel Ripley continued to serve, losing most of the pigment in his face from severe sunburns while stationed above the Arctic Circle.

Official services were held Novemeber 7th, 2008 at the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, and interment in the Academy Cemetery.

In addition to his son, Colonel Ripley is survived by his wife, Moline; three other children, Mary D. Ripley, Thomas H. Ripley and John M. Ripley; a sister, Susan Goodykoontz; and eight grandchildren.

* * * * *

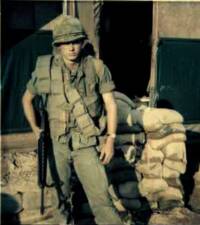

Then Capt. Ripley was Commanding Officer of Lima Co. 3rd Battalion, 3rd Marines in 1966-67 in Vietnam. His association with Lima Company and the 3rd Battalion continued througout his life.

Many of his comrades from Lima Co. and the Bn were in attendance for his services, and he is fondly remembered by all.

Rick Marts assembled a memorial series slide show of Rip's time with 3/3, his services, and a reunion of his Lima Co. alumni in March 2007. The links below are to those presentations:

Veterans Day memory: Marine hero's passing

BRADENTON — The news item scrawled swiftly along the bottom of Ron Darden's TV set, and he almost missed it. Retired Marine Col. John Ripley, a decorated Vietnam War hero, was dead. Darden, 60, sat bolt upright, memories flooding back from that conflict in which he served from July 1967 to September 1968.

“I've honestly tried to forget,” said the 1966 Manatee High School

graduate and Silver Star and Purple Heart recipient.

“It was a difficult war and a difficult time for our country.”

There was no forgetting Ripley, who died Nov. 2 in Annapolis, Md.,

at the age of 69.

He was Darden's commanding officer.

“A Marine's Marine,” said the retired mailman.

“He was the closest thing we had to a living legend ... ” John Grider Miller, another retired Marine colonel and author of “The Bridge at Dong Ha,” told the Los Angeles Times.

Darden remembered his captain in a different setting.

The Bradenton native was a lance corporal, a 19-year-old rifleman in “Ripley's Raiders,” the nickname of Lima Company in Third Battalion, Third Marines.

Wounded two months after he reached Vietnam, Darden was returned to the front and pulled guard duty his first night.

It was the first time he met Ripley one on one.

“I'm in that hole 20 minutes, here comes this shadow down the line. I challenge him. It was the skipper,” Darden said. “He hopped down in the hole and was there the whole watch, just talking to me. He wanted to know about my folks, where I came from, whatever else.

“Right before my watch ended, I said, ‘Skip, I want you to know I was real apprehensive about coming up here. I was scared.' He said, ‘I'm scared every day. I don't want a man in my platoon who isn't scared, but I want you scared at the right time. We can't be scared when we're out there running after somebody.'”

Ripley's loyalty to his Marines manifested itself in many ways.

Darden cited the long letters to families of fallen Marines.

“Skip would write to their folks to tell them what good people their sons were,” he said. “He'd write letters home for people still there, too, wanting them to know he was going to take care of them the best he could.”

One such letter went to the family of a Marine saved by Darden.

It was Sept. 7, 1967.

Quoted in Otto Lehrack's “No Shining Armor. The Marines at War in Vietnam,” Ripley told how Darden ran 30 meters to rescue the wounded Marine and, while lifting him in a fireman's carry, got shot by the same NVA soldier:

“It blew (Darden) backwards, but he kept to his feet, grabbed the muzzle of this weapon ... wrenched it away from him, with Wolfe on his shoulder, and beat that ... to death.”

Darden, whose life was saved because the bullet struck his full canteen first, minimized his own heroics.

Rather, he credited Ripley and what he expected of his Marines.

“You didn't want to let him down,” Darden said. “He was a hero, an absolute hero.”